by Dennis Crouch

Google v. Hammond Development, — F.4th — (Fed. Cir. 2022)

We have an important IPR collateral estoppel decision from the Federal Circuit. The basic outcome here is that issues litigated and decided in one IPR will be seen as fixed and finally decided as between the parties in future IPRs. For family member patents, the courts will ask if the first case answered the same patentability questions at issue as the second case. Preclusion decisions should not be taken lightly because they bar a party the opportunity to defend its rights in court.

Hammond sued Google for infringing a family of three patents and that case is still pending in Waco. Google responded with three IPR petitions. For two of the patents, the PTAB sided entirely with Google and found the claims obvious. Hammond did not appeal those findings. In the third patent–the one at issue here on appeal–the PTAB issued a split decision with six of the thirty claims surviving, including claim 18 in US10270816.

Google’s argument on appeal: Google argues that the issues of patentability with regard to claim 18 of the ‘816 are identical to those already decided by the PTAB in its prior decision invalidating a parallel claim in a family-member patent. Since the issue was already litigated and decided in the first case, Hammond is estopped from relitigating that same issue.

The two patent claims are not identical, but are quite close. Here, the Federal Circuit found that to be good enough based upon prior precedent that issue preclusion can still apply despite language differences in the claims. The question is whether the differences “materially alter the question of invalidity. Ohio Willow Wood Co. v. Alps S., LLC, 735 F.3d 1333 (Fed. Cir. 2013).

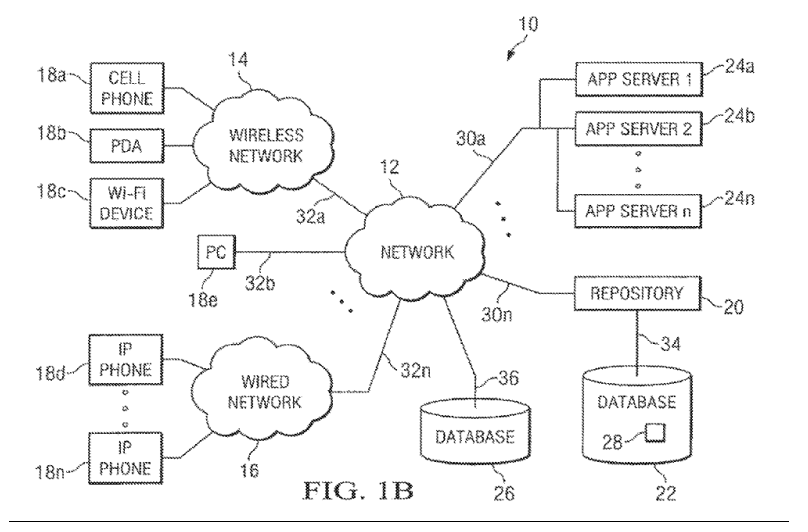

Here, the appellate court identified the differences in the claims and found them insignificant. That conclusion appears shaky somewhat shaky. My reading of the claims is that the previously invalidated claim required certain activities on “one or more application servers.” On the other hand, the claim at issue now expressly divides the activities between a “first application server” and a “second application server.” Thus, for these elements, the already invalidated claim is broader and, in my view, shouldn’t preclude the patentee from arguing those differences. In its analysis, the appellate panel satisfied itself by pointing to a conclusion in the first case that “distributing software applications across multiple servers was well known to the artisan.” But, that conclusion does not appear to directly implicate the specific first and second server configuration as claimed. But, the Federal Circuit is the one that decides, not Crouch.

Collateral estoppel questions always involve at least two cases, and the question is whether some decision in the first case precludes relitigation of an issue in the second case. Federal Circuit doctrine bars the party from re-litigating an issue of fact or law if the following four elements are met:

- The issue in the second case is identical to one decided in the first action;

- The issue was actually litigated in the first action;

- Resolution of the issue was essential to a final judgment

in the first action; and - The party being estopped had a full and fair opportunity to litigate the issue in the first action.

In re Freeman, 30 F.3d 1459 (Fed. Cir. 1994) (in the context of litigation). In this case, the patentee admitted element 2-4, and only challenged the first prong. As noted above, the appellate panel disagreed and found the first prong met.

Timing is a big issue in these cases. The general rule is that issue preclusion attaches as soon as the first case is made final. At times, that “made final” element can be a bit confusing–does it apply at the point of the final written decision by the PTAB, once the Director denies review, or only once all appeals are exhausted? Here, the Federal Circuit did not address that issue since the appeals in the first case had already been exhausted (Hammond did not appeal). Once the first case is final, collateral estoppel will immediately apply and preclude arguments even in parallel ongoing litigation.

The collateral estoppel decision eliminates two more of Hammond’s claims, but the patentee still has four claims that have survived. Hammond may still see this as a partial win. When it comes to patent litigation, the patentee needs just one claim able to run the gauntlet of validity, enforceability, and infringement. We’ll see how that works once the case moves forward before Judge Albright.